This project articulates the importance of preserving adobe structures in San Antonio. In it, Shine identifies and maps adobe structures that remain today using an accessible digital platform. This project incorporates community engagement including stories of local residents of San Antonio and providing public workshops.

Adobe structures vary in appearance depending on where they are located in North America. This project focuses on adobe structures in San Antonio. Most adobe structures that existed and still exist in San Antonio were made with adobe bricks. They do not look like the stereotypical adobe structures seen in West Texas and on Pueblo reservations in New Mexico. Understanding that this research specifically focuses on San Antonio adobe is essential for a number of reasons: 1) Little research has been done on adobe structures in San Antonio, 2) Contemporary and historic adobe structures possibly exist because of the cultural and ethnic diversity in San Antonio, and 3) Adobe uses ingredients that are available to the builders. The adobe structures found in San Antonio are geographically specific because of the ingredients and style implemented during construction. There are common misconceptions of “mission revival” architecture being adobe because of the stucco and round edges that look similar to adobe in West Texas and New Mexico. However, this architecture is actually just designed to recreate the adobe aesthetics without the ingredients of adobe structures.

This project adds a narrative to the little-known history of San Antonio by creating a StoryMap through ArcGIS. This project uses the SpyGlass StoryMap technique, which creates a comparison between two map layers, one containing outlines of blocks where adobe structures existed from the late-1880s to the early-1900s to a heat map of where adobe exists currently in 2019. The earliest Sanborn Map that she used is from 1885 and the latest one is from 1924. The maps provide links and tabs to click on to find more information about adobe structures that exist and what is being done with the adobe that was preserved.

Maps have a complicated history because they have various utilizations: from Bird’s Eye Views to propaganda for the military. However, maps can also provide insight and apply a new lens to history when using Geographic Information Systems mapping technology. Digital history approaches to conveying public history can have many pros and cons, especially when considering accessibility. The combination of spatial and digital history lets me, as a public historian, understand the history of adobe through a new lens. Space and place play an important role in history. This form of mapping targeted at the public is a broad source for community engagement.

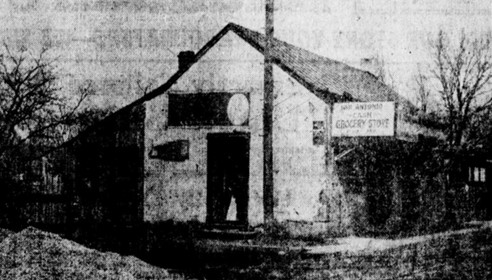

After gathering, analyzing, and mapping out all the locations of potential adobe structures, Shine began driving around San Antonio to the hotspots and addresses that were found. Once structures were located, she knocked on the doors of those living there or in the area if no one was home or living there. For the homes that were not occupied or unsure, she checked the foundations where it was cracked to attempt to see what was underneath the stucco and plaster. There is no other way of knowing what is or is not adobe than looking underneath because adobe could not remain exposed to the elements or it would deteriorate and become damaged quicker than it is protected by the stucco/plaster. The oldest adobe structures she found were built in the early eighteenth century. These structures are known as the Spanish Governor’s Palace and the Alamo. The palace is not difficult to find because of the old Spanish structure in the middle of the urban development, however, the adobe at the Alamo is a bit more complicated. The adobe remains are part of the original wall around the mission.

The project built interest with the Esperanza Center through the eventual display of the digital project embedded on their website to connect more people to both the Esperanza Center’s and Shine’s initiatives. The center hosted an adobe-making workshop that Shine scheduled with them. She met with the center once a month to update the project’s progress, and the director, Graciela Sanchez, provided guidance and critiques that helped when there were challenges in the project.

Articulating the importance of adobe helps gain awareness and can eventually produce a call for action to preserve and protect the structures that are left. The project hones in on a specific topic and attempts to use concise yet inclusive language to appeal to a larger audience. Raising awareness that this history was not left in the past but still exists today can be an example to the community that the story of San Antonio is not complete. Protecting and preserving adobe structures also helps the multicultural and multiethnic history that San Antonio has persisted throughout time.

You can view Shine’s StoryMap here.