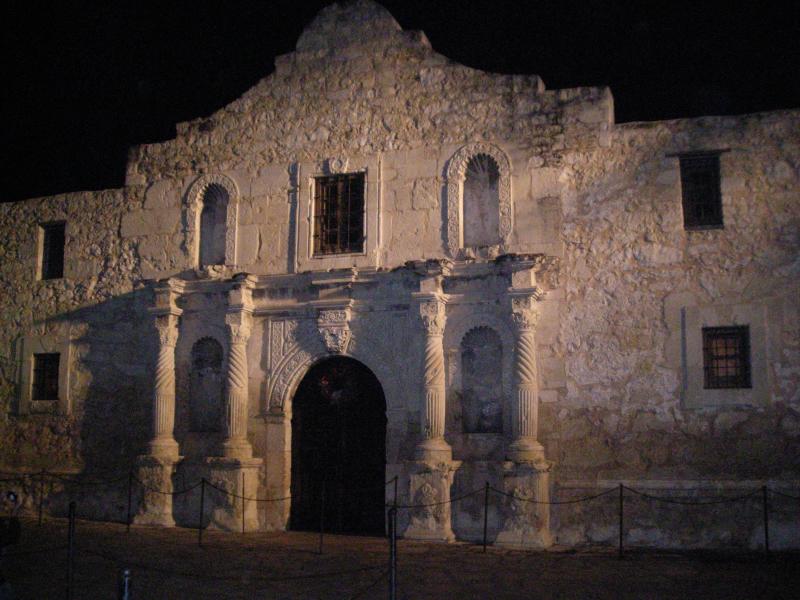

The Alamo is one of the most recognizable monuments in the United States and has nurtured a rich and multicultural history for the last three centuries. Exhibit panels and programming at the Alamo encourage visitors to learn of the Anglo-Texan experience in Texas, provide a cursory and almost vilifying portrayal of Mexico and demonstrate neglect for Texas Indian history. While working as a guide at the Alamo, Gabriel rationalized how to go about addressing this need. Given the complete absence of Texas Indian history, he decided that visitors must have historical context on Texas Indians to understand their history at the missions. This project provided the following: a contextual platform for visitors to acquaint themselves with Texas Indian history, present Native Americans as the main historical figures of the Spanish colonial missions, and increase awareness of the threats against Texas Indian heritage and history at the Alamo.

Despite their undeniable influence on Texas history, the history of Texas Indians is under threat by museums that fail to present their histories. Negligence to present this story on equal terms with those of Anglo-Texans is a historically common practice in the United States. When museums seek expansion with financial motivations in mind, money begins to dictate which histories matter, which endangers perspectives like those of the Texas Indians. Tourists Gabriel encountered with an interest in Texas Indian history were left disappointed by the lack of a single exhibit panel on the site to educate them on the subject. Despite the oversight, there are over a dozen trained docents and living historians at the Alamo who have expressed to him their interest in Texas Indian heritage and history and their frustration at its absence from the site.

The lack of any preexisting exhibit panels at the Alamo about Texas Indians made the creation of this project rather difficult. Understanding that visitors to either the Alamo or the exhibit may lack education about Texas Indians influenced me to expand the project scope. An exhibit can only be so long before the visitor will grow weary and stop processing the information provided. The exhibit has four exhibit areas: Introduction: Discussing Texas Indian History at the Alamo, Paleoindians in Texas, Cultural Diversity in South Texas, and Preserving Texas Indian History. Originally, there were plans to add a fifth section, Texas Indians at the Spanish Colonial Missions, but that is very much dependent on access to primary sources currently held in private collections. Gabriel developed this exhibit by seeking out how to forge stronger partnerships with more Alamo stakeholders, wanting their insights and their assistance with the interpretation of existing secondary sources. He also wanted to include more primary source documents and photographs from the AITSCM archive, recognizing this project was somewhat dependent on amicable relations between AITSCM and the Alamo Trust.

The Alamo has the potential to serve as a site that encourages diversity in urban development, cultural exhibits and events to be developed, and art to flourish. The result of such efforts would be the evolution of San Antonian identity to reflect a far greater demographic and establish San Antonio as the preeminent cultural landmark in Texas. The Alamo’s fame as a place of history enables it to serve as a nexus of culture at the “Crossroads of History.” Such a place would “recognize the social diversity of the city as well as the communal uses of space,” encouraging far more visitors to feel included in the Alamo’s history. This in turn would likely lead to increased revenues from donations, private donors, and more community partners providing endowments for the preservation of the site.

Due to training as a public historian, Gabriel engaged in community projects that benefit the public at large rather than those that benefit the niche audience of academics. Both pursuits have value, though the goal of this project falls into the former category. At the same time, his being an upper-middle-class, Caucasian male caused questions about the legitimacy of the role of the interpreter in Native American history. As a result, relying on individuals with Indigenous American ancestry for the interpretation of evidence within this project proved insightful. Working on this project taught him to adopt more empathic listening techniques with communities whose histories are being neglected.